- Log in to:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

- Sign up for:

- Community

- DigitalOcean

By Adrien Payong and Shaoni Mukherjee

Introduction

In recent years, artificial intelligence has moved from research labs to real-world applications at a remarkable speed. As a result, our technical ecosystem is rapidly transforming from a world of largely isolated systems to one of interacting autonomous agents. An autonomous agent is a computational system or an AI entity that can sense, reason, and act upon its environment with a high degree of independence. Such agents can negotiate with one another, agree on joint action plans, trade resources and information, and communicate while they work. This is where agent communication protocols come into play.

Agent communication protocols are standards, languages, and message formats that specify how agents interact and communicate. Agents use these protocols to share information, coordinate decisions, and form shared plans. The core concepts behind ACLs have been around for a while in the form of classic multi-agent systems (MAS) and the academic research around FIPA ACL and KQML. However, the landscape is changing rapidly as we enter a new era of large language models, JSON-based APIs, and agent orchestration frameworks like OpenAI’s MCP, LangGraph, AutoGen, and Swarm.

In this article, we will cover the basics of agent communication languages and the anatomy of an agent message. We will discuss real-world use cases of agents communicating using both classic ideas and cutting-edge protocols that tie into the tools developers use today.

Keys Takeaway

- Shift from Monolithic to Multi-Agent Ecosystems: AI is moving from monolithic systems to multi-agent ecosystems. These ecosystems consist of numerous autonomous agents that can reason, act, and communicate. Protocols are used for agents to communicate with one another.

- Communication Requires Structure and Semantics: Agent communication languages (FIPA ACL, KQML, etc.) added performatives, content structure, and ontologies to make the intent and meaning explicit. These principles still inform how agents communicate today.

- Modern Protocols Use JSON and APIs: The frameworks use JSON contracts, schemas, and protocols such as MCP (Model Context Protocol) to formalize communication between LLM-based agents and tools. This improves clarity, interoperability, and security.

- Security, Trust, and Observability Are Central: Modern systems embed permission controls, sandboxing, and logging to handle misaligned or malicious agents. Observability through message IDs, tracing, and replay is key for debugging and transparency.

- Standardization Enables Collaboration at Scale: The principles of MAS and ACLs live on in today’s ecosystems (e.g., LangGraph, AutoGen, Swarm), where standard protocols and well-defined message structures allow scalable, safe, and interoperable agent communication.

What is Agent Communication?

Agent communication in multi-agent systems is the process of exchanging messages between agents in order to collaborate. Similar to humans, artificial agents use a communication language or protocol to “talk” to one another and to others in their environment. These messages are structured forms of information, not just raw data. For instance, an agent can send a message to another to make them aware of a fact or to request that another agent perform an action.

Why Agents Need Protocols

Messages sent outside the agreed format might be ignored, rejected, or misinterpreted by other agents. Here are a few reasons why protocols are needed:

- Interoperability: A standard protocol enables agents written by different developers or using different frameworks to talk to each other. It serves as a universal translator for agent communication.

- Clarity of Intent: Protocols specify types of messages (called the performative or speech act), such as request, inform, propose, etc. This is part of the metadata or framing around a message that indicates what the sender intends to do.

- Coordination & Sequencing: Protocols often include conversation management to track message exchanges. A defined communication protocol ensures everyone “speaks the same dialect” – for example, an agent knows that after sending a CFP (call for proposal) message, it should expect to receive either a proposal or a refusal message in response.

- Reliability & Error Handling: Robust protocols include provisions for handling errors or exceptions. For example, an agent that receives an unrecognized or corrupted message may respond with a not-understood performative (in FIPA ACL) or a sorry message (in KQML) to signal that it cannot comply with the request.

- Security & Trust: In open agent systems, a protocol can impose certain constraints (like requiring authentication fields or formalizing contractual steps before an action can be taken).

Classic Agent Communication Models

Early research in multi-agent systems established dedicated languages for inter-agent messaging. Two landmark agent communication languages are KQML and FIPA ACL. They introduced structured message formats and semantics inspired by speech-act theory and have influenced modern protocols.

KQML – Knowledge Query and Manipulation Language

KQML (Knowledge Query and Manipulation Language) was created in the early 1990s as part of DARPA’s Knowledge Sharing initiative. KQML defines a set of message performatives (or verbs) to declare the purpose of a message. Performatives can be thought of as a kind of diplomatic code of conduct for agents.

They include standard actions like ask (query for information), tell (supply information), achieve (request an action, equivalent to “please achieve this goal”), reply (answer a query), and so on.

In KQML, the content of a message is separated from the communication wrappers. A KQML message is a list (parentheses in Lisp-like syntax). The first element of a KQML message is the performative, followed by the message parameters (content, sender, receiver, etc). A KQML message looks conceptually like this:

(ask-one

:sender Agent1

:receiver Agent2

:content "(temperature ?x)"

:language LPROLOG

:ontology weather)

In this hypothetical message, ask-one is the performative (i.e., Agent1 is asking Agent2 a question), the content could be a question (temperature ?x) in some logical language, and an ontology and language field describe how to interpret that content.

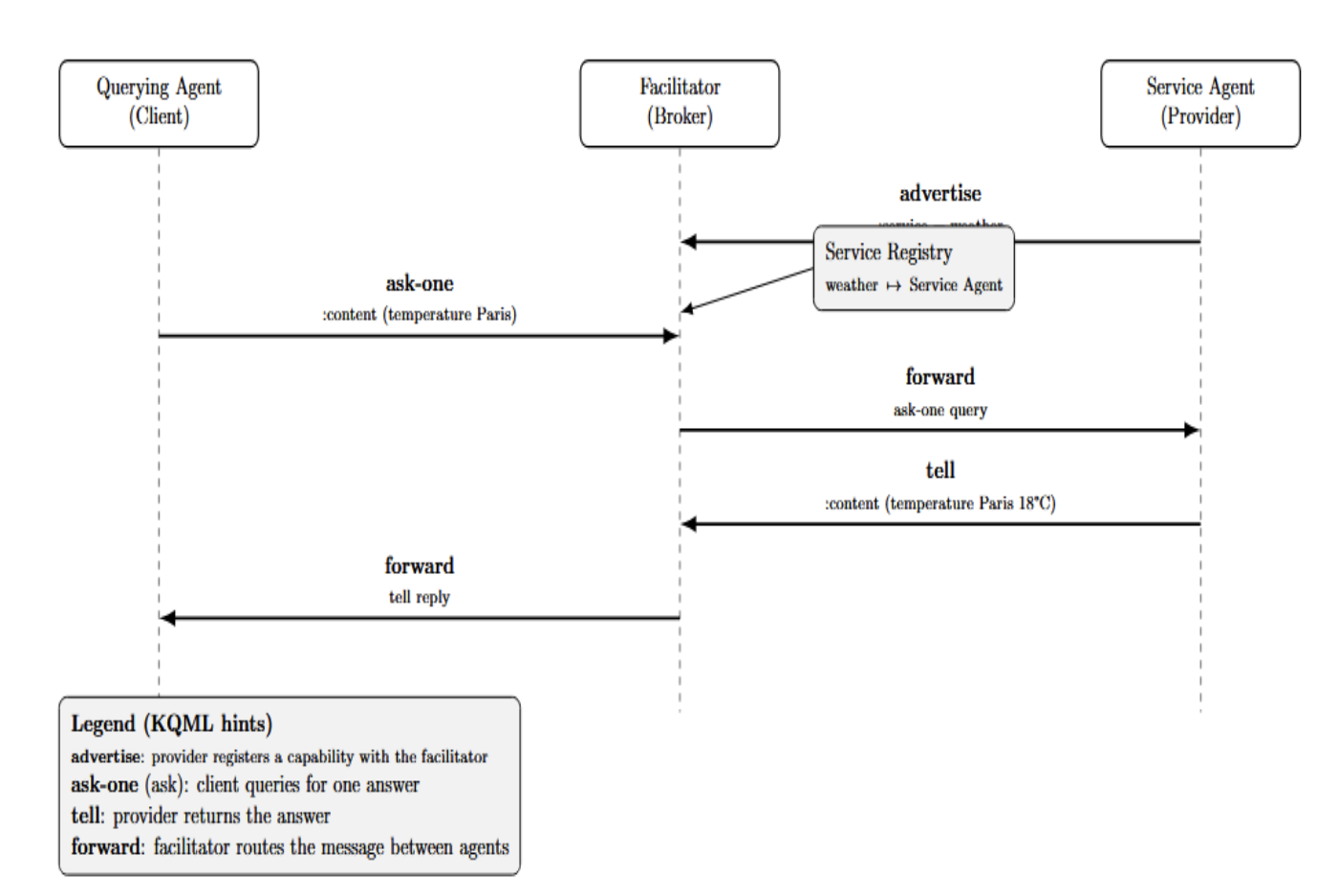

KQML was one of the first to propose the concept of communication facilitator agents. A facilitator is a broker or mediator agents that route messages and help agents find each other. For instance, one agent could register its services using a facilitator. As a result, when another agent sent a query (e.g., with a performative such as ask), the facilitator could forward the request to the registered agent that could answer it.

KQML included performatives for these networking activities (e.g., register, forward, and broadcast). It also supported some early patterns for asynchronous messaging: for example, a performative subscribe to request continuous updates when some condition changes.

FIPA ACL – Foundation for Intelligent Physical Agents ACL

The next major standard following KQML was the FIPA ACL, which was widely deployed during the late 1990s and early 2000s. FIPA is an IEEE standards organization whose mission is to develop and publish specifications for interoperable distributed, multi-agent systems. FIPA ACL refined the list of performatives and formalized the semantics based on the agents’ mental states (beliefs, desires, intentions).

It defines a set of about 20 standard performatives (communicative acts). This includes many from KQML as well as some new ones. For example, some standard FIPA performatives include:

- inform – inform another agent of some information (information which the sender believes to be true). This is one of the most common performatives, and it is essentially a factual statement.

- request – request that another agent perform some action.

- confirm / disconfirm – confirm that something is true (or false) that the sender believes the receiver was uncertain of.

- cfp (Call for Proposal) –call for proposals of an action (contract-net interaction).

- propose – make a proposal in response to a CFP.

- accept-proposal / reject-proposal – accept or reject a proposal received.

- agree – agree to perform the action requested (agent will attempt to do it).

- refuse – refuse to perform a requested action (includes reason).

- failure –indicates that an action that was requested by the agent failed to complete.

- query-if / query-ref – make a yes/no query or request a specific item of information.

- subscribe – request a continuous notification (i.e., subscribe to changes of some info).

- not-understood – signal that a message was not understood.

and a few more (such as cancel, proxy (have another agent forward your message to others), etc.)

A FIPA ACL message has a fixed set of parameters (fields). The only required field is the performative. However, a message typically has the following fields: sender, receiver, content, and often other fields such as ontology, language, conversation-id, etc. A FIPA message might be in an abstract representation of this form:

(performative INFORM

:sender Agent1

:receiver Agent2

:ontology WeatherOntology

:language JSON

:content "{ 'forecast': 'sunny' }"

:conversation-id conv123)

The format is very similar to a properly structured business email or letter – you have the sender, recipient, subject (performative type), body content, and perhaps references (such as a thread ID). The ontology field tells you the context or vocabulary in which the message content is expressed, and language might specify the format of the content (could be a logic syntax, or raw text, or JSON, etc).

Message Structure

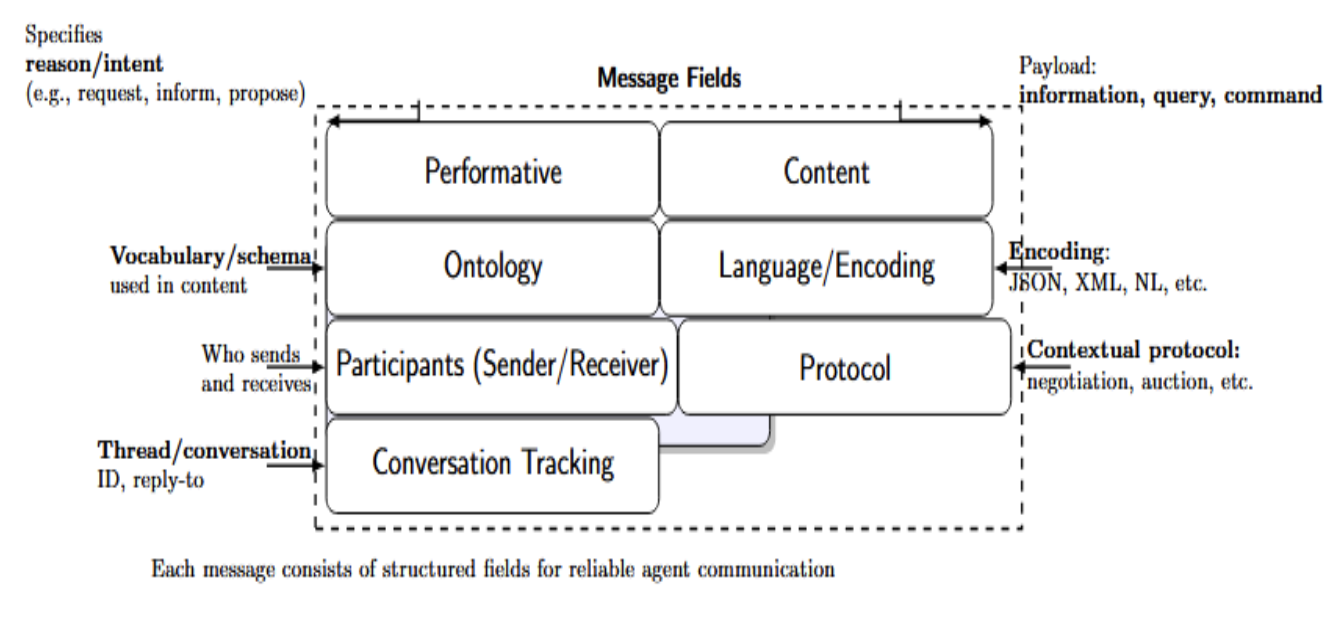

It is worth double-clicking on the overall message structure that evolved from the classic ACLs. This is because the same pattern can be found in most modern protocols (albeit sometimes under a different form, such as JSON fields). The basic elements of an agent communication message are:

- Performative: The kind of communicative act that is being performed. This specifies the reason why the message is being sent. The performative implicitly defines the context in which the message should be processed. (Is it a request for action to be done by me? The announcement of a fact? A proposal for a contract?) In FIPA ACL, the performative is required and is always the first item of the message.

- Content: The message payload, i.e., the actual content of the message – i.e., the information or data being transferred. This could be a proposal, a question, a command, or some domain-specific data. For example, the payload might be “the temperature is 20°C” (information), or “temperature > 30?” (a query), or a command such as “increase thermostat setting to 25”.

- Ontology: In agent communication, an ontology can be simply understood as the vocabulary, or knowledge schema, to which the content conforms. It specifies the terms used in the content and their relationships. For example, agents communicating about a travel plan may reference a “travel ontology” defining what “flights” are, what “price” refers to, the structure of a “booking” object, etc.

- Language (or Encoding): The language parameter identifies the syntax or encoding of the content. Is the content a natural language string? Is it a JSON object? Is it a Prolog logic clause? Is it an XML document? By specifying the content language, the sender instructs the receiver how to parse the content field.

- Participants (Sender/Receiver): Of course, each message will carry information about who is sending it, and who should receive/process it. One-to-one communication is simple (one sender, one receiver), but with a broadcast or multicast, the protocol may allow a list of receivers or a group identifier.

- Protocol: Sometimes a message is part of a predefined interaction protocol (eg, a contract net negotiation or an auction). A protocol field can be used to identify which protocol context this message belongs to. This allows the receiver to interpret it in context (eg, if you receive a proposal and the protocol field says “contract-net”, you know it’s a bid in a contract net context rather than an unsolicited proposal).

- Conversation Tracking: Agents performing multi-step conversations may want to tag messages with an identifier so they can be linked into threads. Fields such as conversation-id, reply-to, etc., are intended to help keep track of multiple messages. For example, if Agent A asks Agent B two questions (two separate requests) and B responds, the conversation identifiers allow A to associate the correct response with the correct question.

Modern Evolution — LLM Agents & JSON Contracts

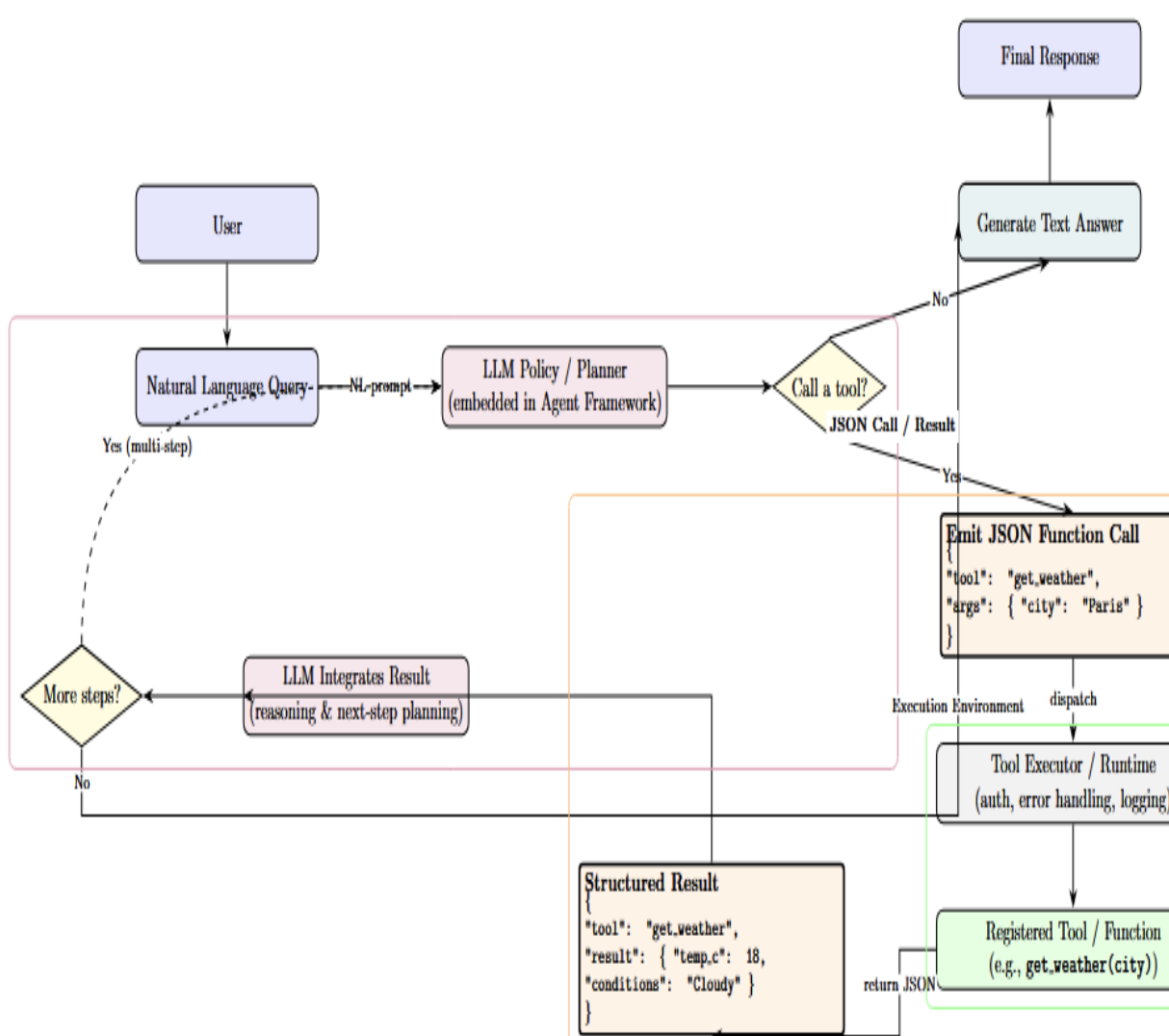

Large language models such as GPT‑4 and Claude have introduced the first generation of natural‑language‑based agents to the mainstream of software. Modern Agent frameworks embed LLMs into multi‑step workflows and need a way to represent and execute tasks in response to natural language queries. Tool/function calling is the bridge mechanism: rather than producing plain-text output, the LLM “emits” a structured JSON describing a function call. When the LLM “chooses” to call a tool, it produces a JSON object with the function name and arguments.

This image depicts a simplified workflow. The user query is processed by the LLM agent. The agent can either produce a text response or make a function call to an external tool. Function calls are emitted as a JSON document that specifies a particular tool and a dictionary of key/value arguments (for example, the “get_weather” tool with an argument for the city name “Paris”). The call is processed by the tool runtime, which authorizes and forwards it to the registered tool function. The tool produces a structured result (for example, a JSON object containing temperature and conditions) that is passed to the agent. The LLM takes the tool output and uses it to either produce another plan or a response.

The JSON contract pattern decouples the LLM reasoning from the execution environment. Here, the LLM independently determines when to call a tool. Additionally, external code is responsible for the call execution (with appropriate authentication, error handling, and logging). The structure format avoids injection attacks, and the message can be easily parsed. Relative to FIPA’s abstract syntax, JSON has broader support across programming languages and can be readily integrated with web APIs.

However, this model only implicitly specifies the performative semantics (i.e., intent/kind of message). As a result, this can lead to some ambiguity of intent relative to the explicit performatives in an agent communication language like KQML or FIPA-ACL. Overall, JSON contract patterns offer useful features for modern LLM workflows, at the cost of trading explicit communicative acts for natural language-driven control.

How MCP (Model Context Protocol) Fits Here

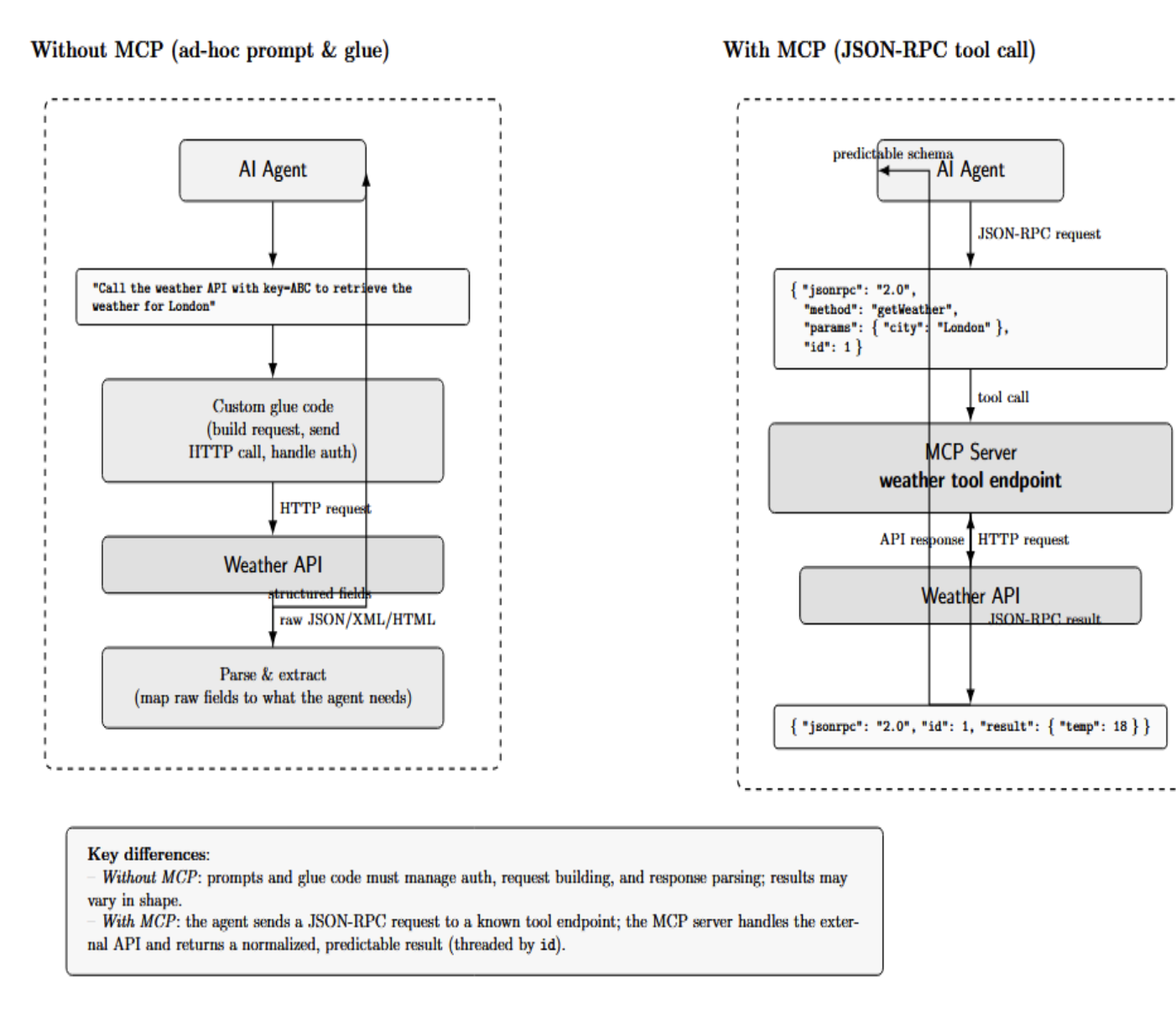

Essentially, MCP is a proposed open standard for how AI agents (LLMs, particularly) can be connected to tools, external data sources, and other agents in a structured way. OpenAI, Anthropic (and others) are standardizing and promoting this as a common interoperability layer for AI.

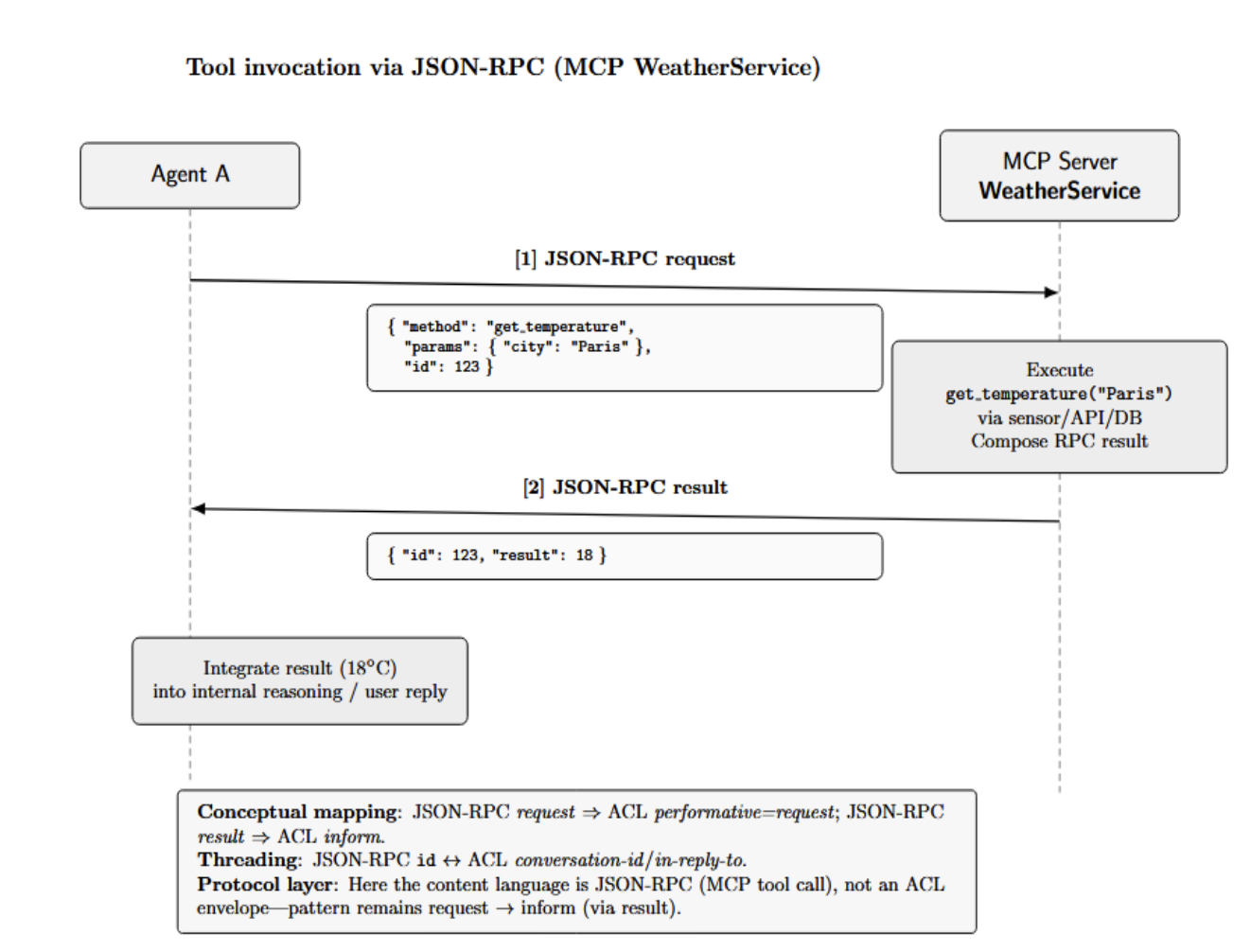

Under the hood, MCP is built on top of JSON-RPC 2.0, a lightweight remote procedure call protocol that uses JSON. In simpler terms, MCP is a set of agreed-upon message formats that enable an AI model to make a request like “Call tool X with these parameters” and receive the result in a predictable JSON format, regardless of what the tool is or who built it.

For example, say you have an AI agent that needs to get weather data. Without MCP, a developer might write a custom prompt like: “Call the weather API with key=ABC to retrieve the weather for London” and then let custom code parse the result.

With MCP, the agent could instead make a JSON-RPC request to a “weather tool” endpoint that’s been exposed by an MCP server: e.g., {“jsonrpc”: “2.0”, “method”: “getWeather”, “params”: {“city”: “London”}, “id”: 1}. The MCP server would know how to handle that (probably making a call to an actual weather API behind the scenes) and then return a JSON result. The agent would get that result back in a predictable format.

MCP is an important part of the modern agent communication picture, with many of the advantages of traditional ACLs (standardization, well-specified expected behaviors) extended to the modern setting of AI agent tooling. While it focuses on the agent tool side, it standardizes a large portion of agent communication.

Where Are Agent Communication Protocols Used? (Examples)

Agent communication protocols may seem a bit abstract and theoretical. However, there are numerous instances where they are actually used (and needed) in some of today’s most advanced AI systems. Let’s take a look at a few examples and use cases:

| Domain / Scenario | How Agent Communication Is Used | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Automation & Robotics | Multiple agents (robots/machines) coordinate tasks, negotiate assignments, and share status. Standardized protocols enable cross-vendor interoperability in factories and infrastructure. | FIPA ACL on platforms like JADE; industrial process management, smart grid/city coordination; overview: |

| Distributed AI & Web Services | Early web-service orchestration explored ACLs so intelligent agents could discover/invoke services semantically (beyond raw API calls). | Registries like UDDI, SOAP, REST / JSON |

| Collaborative Multi-Agent Systems | Teams of agents coordinate roles/strategies via message types (e.g., inform world state, request plays) for joint decision-making. | RoboCup Soccer Simulation; decentralized traffic management (vehicles/lights as agents) |

| Modern LLM Agent Orchestration | One agent plans, another executes; text-based protocols or structured calls pass tasks/results. Tool use mediated by standardized message formats (e.g., MCP). | AutoGPT, GPT-Engineer; AutoGen |

| Agent Frameworks in Products | Productized assistants split responsibilities across internal agents (dialogue, calendar, email). They exchange structured “action” messages that the runtime executes. | LangChain Agents, LangGraph; actions/observations in JSON-like formats |

| Cross-Platform AI Agent Collaboration | Agents from different vendors interoperate via shared protocols, delegating tasks without bespoke glue. | Model Context Protocol (MCP) communicates with external tools and other agents. |

| Research Simulations & Games | Agents negotiate, plan, or coordinate within simulations/games; natural-language dialogue may be paired with internal protocol/state tracking. | Meta’s CICERO is an AI agent built to play the complex strategy game Diplomacy by integrating natural-language dialogue with internal planning and state tracking. |

| Swarm AI & Multi-LLM Swarms | Many simple agents exchange lightweight signals; protocolized turn-taking/context sharing yields emergent behavior and brainstorming. | OpenAI Swarm; open-source Swarms (production orchestration) |

Challenges

Agent communication protocols provide structure but come with challenges. The table below maps each issue to practical mitigations:

| Challenge | Why it Matters | Mitigations / Design Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Misalignment & Semantics | Classic assumptions (e.g., truthful/rational agents in FIPA ACL) often don’t hold in open systems. Agents may send false or misleading information messages (by error or malice); verifying intent and truth is hard. | Limit agent capabilities; permission-gate tools; require human-in-the-loop for critical actions; add verification steps (evidence, cross-checks), reputation scores, and consensus protocols before trusting facts. |

| Security | Agents can request actions; a malicious/broken agent could trigger harmful operations (incl. prompt-injection). Needs authn/authz and secure transport in distributed settings. MCP scopes tool visibility and can require explicit user permission. | Authenticate senders; role-based authorization; encrypt channels; sandbox agents; validate and rate-limit messages; inspect payload size/shape to prevent abuse (e.g., DoS via oversized content). |

| Overhead & Efficiency | Structured protocols (e.g., CFP → propose → accept → inform) add message volume/latency. Multi-agent setups can consume far more tokens (reported up to ~15× vs single-turn). | Tune granularity of exchanges; batch messages; compress content; share a memory/store rather than repeating context; stream results; parallelize where safe; prune/TTL old conversation state. |

| Complexity & Error Handling | Long dialogues require threading and state; replies must map to the right request. Missed messages or off-script LLM outputs can derail coordination. | Use conversation IDs, in-reply-to, deadlines; implement retries/backoff and alternate plans; define explicit error/exception messages; add guardians that normalize/offramp off-spec outputs. |

| Standardization vs. Flexibility | Universal protocols can feel rigid/overkill; domain teams prefer simpler, bespoke formats. Fragmentation across frameworks (LangChain, AutoGen, Swarm, etc.) persists; convergence is uncertain. | Adopt a core standard where possible (e.g., JSON schemas, MCP) and allow domain extensions; provide adapters/bridges; version your contracts; document ontologies; deprecate gracefully. |

| Observability & Debugging | Many agents & messages make failures hard to diagnose (who didn’t respond? which message failed?). Structured protocols enable instrumentation; MCP logs allow replay; some frameworks offer dashboards. | Log every message with IDs/timestamps; add tracing and visual conversation threads; capture tool call transcripts; surface metrics (latency, error rates) per agent; enable replay and time-travel debugging. |

| Security (cont.) & Inter-Agent Trust | Cross-party agents may need authenticity and content safety guarantees. LLM-to-LLM interactions risk injection/deception; trust must be earned and maintained. | Cryptographic signing/verification; content filtering and constraint prompts; zero-trust defaults; multi-source validation; reputation/attestation for agents; quorum/consensus for critical facts/actions. |

Quick Example Message Exchange Format

Now, let’s combine everything we’ve seen with a very simple example. Assume there are two agents involved in the system. Agent A is a client. Agent B can provide data. Let’s assume that Agent A wants the temperature in Paris and that this is information Agent B can provide.

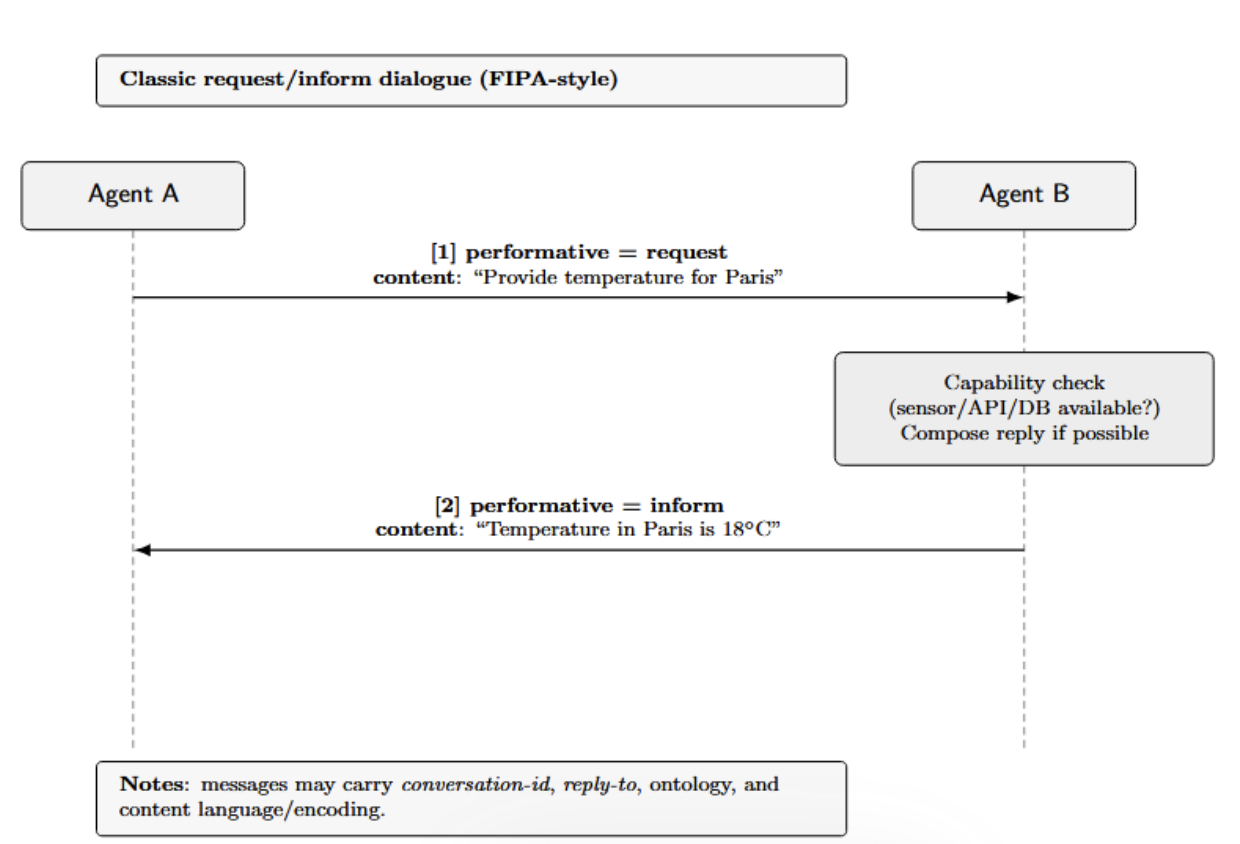

In a classic protocol, Agent A might send a message with performative = request, content = “Provide temperature for Paris”. Agent B, upon receiving this message, would check whether it can provide this information. It might then answer with performative = inform, content = “Temperature in Paris is 18°C”. A high-level view of the dialogue can be seen below:

In a FIPA ACL format, the messages could look like:

- Agent A → B: (request :sender A :receiver B :content “query-temperature(Paris)” :ontology Weather)

- Agent B → A: (inform :sender B :receiver A :content “temperature(Paris,18)” :ontology Weather)

This shows the structured approach: A’s message is a request (so B knows it should perform some action). B’s response is an inform (so A knows this is the response, not, e.g., a rejection or a question).

Using a modern JSON-RPC style (MCP), Agent A could instead invoke a tool. E.g. A sends a JSON RPC call to a “WeatherService” MCP server: {“method”: “get_temperature”, “params”: {“city”: “Paris”}, “id”: 123} and the MCP server (Agent B’s role) replies: {“id”: 123, “result”: 18}. Agent A then weaves that into its own reasoning or response. In that case, the protocol is different (JSON instead of an ACL message), but it’s conceptually still the request and inform pattern - only that the inform part comes as an RPC result.

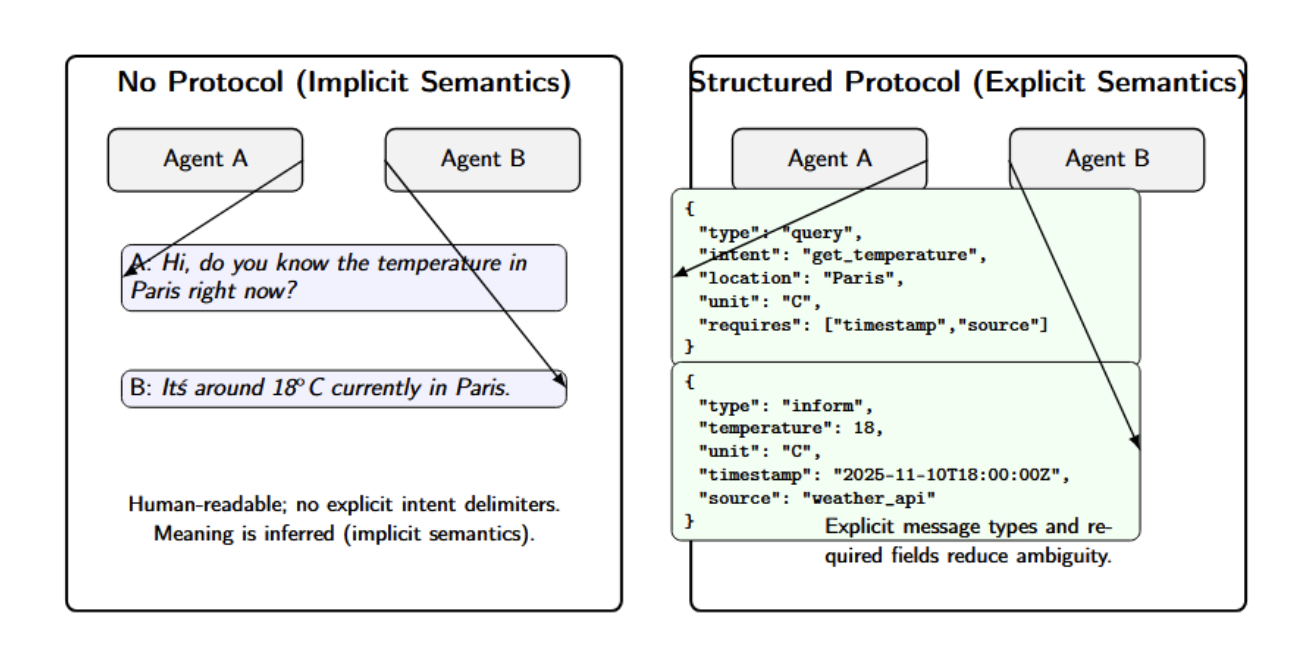

Using plain language (LLM-to-LLM): A conversation between two LLM-based agents without a protocol may look like:

- Agent A (as text): “Hi, do you know the temperature in Paris right now?”

- Agent B (as text): “It’s around 18°C currently in Paris.”

This is obviously human-readable, and it works (informally) because both models are pretrained to understand English. But there are no explicit intent delimiters, as a protocol would have. We are relying on implicit semantics. In a structured approach, nothing is implicit: message types and expectations are declared.

The examples above are simplistic, but hopefully they demonstrate that agents can “talk” to each other in different ways. These protocols become even more important as the systems scale (numbers of dozens of agents working together on sub-tasks, or tools with complex inputs/outputs)

Conclusion

Agent communications have been key to connecting the AI systems we have today. There is a winning recipe that has gained traction. You can use simple, schema-based message shapes (JSON contracts or MCP), with a clear performative intent (fields in the messages indicating the desired action, similar to FIPA performatives). Focus on security and access control from the beginning and invest in observability (message IDs, tracing, replay, etc). While the original principles of MAS (FIPA/KQML) still guide the semantics (who is asking, who is telling, under what ontology), the recent systems (LangGraph, AutoGen, Swarm) provide the practical ways to implement them at scale.

For those working on systems right now: pick a minimal starting point (inputs/outputs, IDs, timeouts), start shaping more structured tool calls, and build up to standardized semantics to allow agent-to-agent interoperability. Measure the overhead (token and latency costs) and protect against failures (sandboxing of unsafe actions), and iterate to cover failure modes. This doesn’t need to be a perfectly coherent protocol; it must reliably allow collaboration between autonomous components.

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

About the author(s)

I am a skilled AI consultant and technical writer with over four years of experience. I have a master’s degree in AI and have written innovative articles that provide developers and researchers with actionable insights. As a thought leader, I specialize in simplifying complex AI concepts through practical content, positioning myself as a trusted voice in the tech community.

With a strong background in data science and over six years of experience, I am passionate about creating in-depth content on technologies. Currently focused on AI, machine learning, and GPU computing, working on topics ranging from deep learning frameworks to optimizing GPU-based workloads.

Still looking for an answer?

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

- Table of contents

- **Introduction**

- **Keys Takeaway**

- **What is Agent Communication?**

- **Why Agents Need Protocols**

- **Classic Agent Communication Models**

- **Message Structure**

- **Modern Evolution — LLM Agents & JSON Contracts**

- **How MCP (Model Context Protocol) Fits Here**

- **Where Are Agent Communication Protocols Used? (Examples)**

- **Challenges**

- **Quick Example Message Exchange Format**

- **Conclusion**

- **References**

Deploy on DigitalOcean

Click below to sign up for DigitalOcean's virtual machines, Databases, and AIML products.

Become a contributor for community

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

DigitalOcean Documentation

Full documentation for every DigitalOcean product.

Resources for startups and SMBs

The Wave has everything you need to know about building a business, from raising funding to marketing your product.

Get our newsletter

Stay up to date by signing up for DigitalOcean’s Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

New accounts only. By submitting your email you agree to our Privacy Policy

The developer cloud

Scale up as you grow — whether you're running one virtual machine or ten thousand.

Get started for free

Sign up and get $200 in credit for your first 60 days with DigitalOcean.*

*This promotional offer applies to new accounts only.